Paul ConnorArtist Talk Accompanying Essay

Taken to the Edge

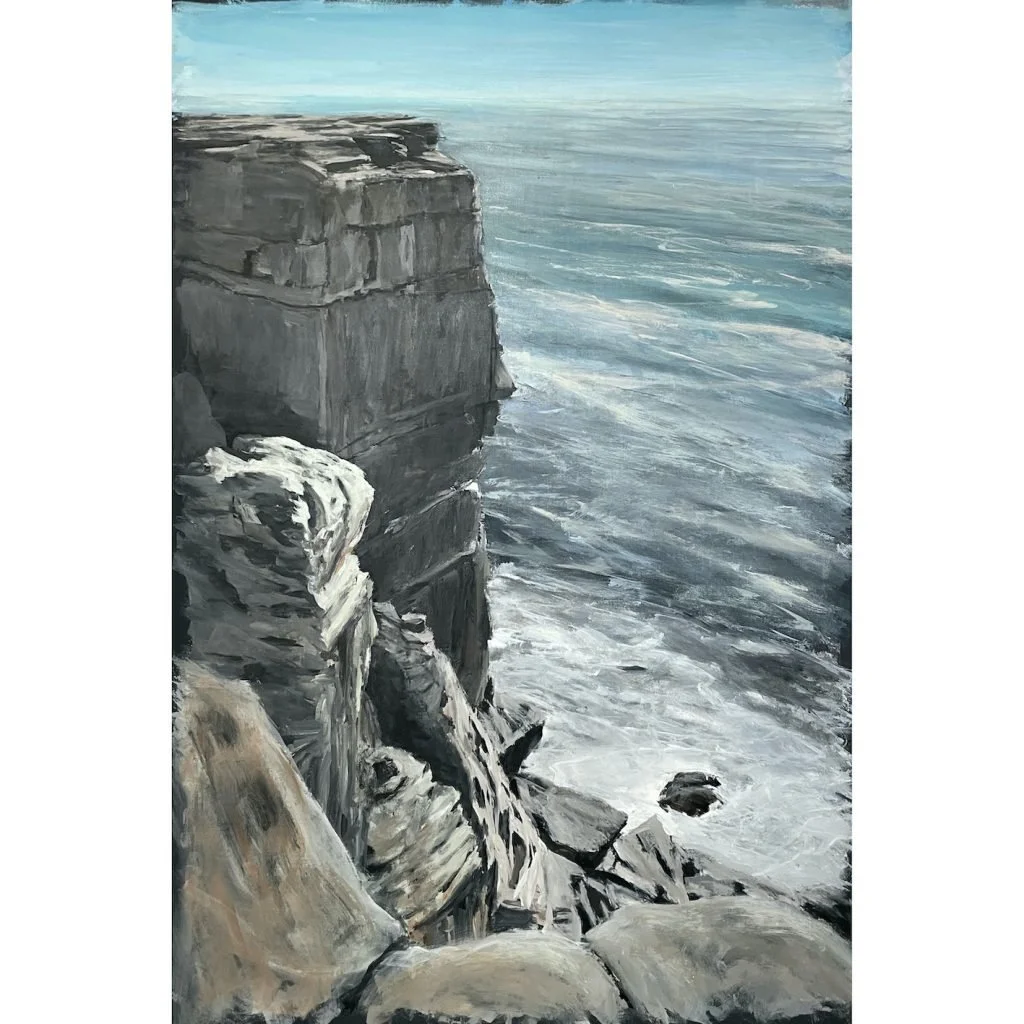

Edge - the outer / furthest point of something; The line where an object or area begins or ends, Middle English – cutting side of a blade, border; Indo-European – sharp pointed.Paul Connor takes us to the edge....To the sheer edge of the tamed land and the vast wild oceanTo the edge of time and ourselvesWe stand on the precipice, where the First Peoples watched the ominous white sails chart the coast, round the headland and possess their lands. A landmark of arrival claimed thenceforth, and the edge of the penal colony from which to flee. A cove found, a grid overlaid, a desire to order the natural terrain. A base from which the city grows up, and out. It now proudly glistens in the sunlight, a focal point of topographical splendour, seen from all around. We see in Cliff Study 5, The Quiet Before The Storm at Tarralbe (South Head), the neat creeping suburban pattern [form/ patina], incongruous in its ambitions and scale, is mocked by nature. The domestic picket fence attempts to claim the majestic cliff top before it falls away to the ocean below. Further to the south, is a peninsular with a cloak of mowed grass draped upon it. Nature smirks as small white balls, seeking small holes, are lobbed into its jaws to be blown off course.Cliff edge, knife-edge. Rock strata revealed, forced from the belly of the earth 200 million years prior. Cliff Study 11, The Edge of The Big City (Tarralbe / South Head) shows us

sandstone sheer and brilliant, stroked by rays of light and tickled by wind. Standing as tall as those buildings of the metropolis. A precipice off which we might fall, into or out of time. Geological time, exposed to be seen and read as data. Wind, water, slowly clawing, taunting, taking, eroding. Boulders in Cliff Study 1, No Escape, Hornby Battery (Tarralbe / South Head), sit as evidence of an unfixed edge, a boundary claimed by the sea.The vast ocean, ever present, roaring gently or with vigour, rolling, frothing. It can almost be heard screeching, yearning, in Cliff Study, 10 Vertigo (Tarralbe / South Head). It welcomes majestic creatures as they make their journeys from cooler waters to warm. Glimpsed rising to the surface expelling air, momentarily greeting our world, before sinking back to theirs. Human’s own creatures carrying their cargos of wealth, dots in the distance or behemoths much closer. Some have misjudged, underestimated nature’s power, taken down, to lie silent on the ocean floor, hiding beneath the surface of Cliff Study 8, Threshold, Tasman Sea.A threshold is a place passed over, a crossing into a room, marked by wood or stone. But here we are invited to dwell in the in-between, the place where worlds collide. The threshold between tamed, untamed; known and unknown; land and sea; stability and instability; death and life.Connor has walked this cliff line, contemplated its histories, observed its presence, absorbed its atmosphere, feared its drop, painted its majesty. He pays homage to those who recorded their stories and created galleries in the rocks long before. To the ancient spoken names returning, written and rising again. To men from afar who built roads in servitude and not free to travel. To those who sat in wait in fortified bunkers, scanning the horizon for the enemy, imagined or real, weapons at the ready. Man meeting nature’s hostility.

For Connor it seems a personal quest, to discover, uncover, reveal, to overcome. He confesses to the will required to get out of bed and go to this foreboding place to capture the first light as it greets the rocky face. He says these cliff studies are “an exercise in observation rather than interpretation.” But these are not passive observational records. This clifftop precipice possesses ones being, unsettles and unnerves. Wind, water, atmosphere, pressure, builds around and within. The body is infiltrated, and the mind is emptied; raw emotion drowning reason.The paintings capture a perspective that is sensed and experienced, but never entirely seen. To paint them, was to both be in, and capture danger, residing on the literal edge. The paintbrush conquers the scale, bringing the enormity into reach, and made tangible. At the bottom of these upright

canvases the rocky edge on which we stand is painted with broad strokes, anchoring, or does it? It could almost be overlooked in the expanse of what surrounds. To the top, the horizon touches land, a slither of sky with atmosphere looming all around. The light, hostile or placating, ominous or uplifting. The mass of the cliff face; the geological strata laid bare, standing, bracing, flexing its muscles. Far below, at the base, sea beating, swirling, quarrelling with the rocks, felt deep in our bellies, another world awaits.There is power to what lurks at the edge of the canvases embodying the immensity of what lies beyond. Vastness, terror, fear, wonder, the abys and the sublime. Light seduces and soothes. Within us the edges and boundaries dissolve as the paint layers and masks. Certainty is clouded by uncertainty. Ambiguity seeps in, questions arise. We must surrender to the rise of astonishment and awe, reverential respect, where terror becomes delight.

Kate GoodwinIndependent curator and critic Hon FRIBA, Adjunct Professor (Architecture) USYDClick here to view Paul Connor’s profile and artworks.